In this article

It’s not uncommon for cats to live well into their 20s, and certainly into their late teens, largely thanks to improved healthcare and nutrition, but also as a result of greater awareness from owners. The basic route to providing a positive life for your cat is to ensure good nutrition, provide exercise and enrichment, and make sure that your cat gets veterinary treatment and checkups when required.

As well as contributing to greater longevity, the tips below help ensure your cat lives a more enriched, fulfilling, and enjoyable time throughout their life.

The Life Stages of a Cat

There are four main life stages of a cat, which are consistent with a cat’s maturation and aging process, as well as their nutritional and healthcare needs. These are general guidelines and there will be significant variation between individual cats.

- Kitten – From birth up to approximately a year, a kitten will be dependent first on its mother and then on its human. This is the time when cats develop the most. They burn through a lot of calories and need a lot of protein in their diet. They will usually be spayed or neutered at this stage, and they will learn to use a litter tray while also undergoing early socialization to ensure they develop into well-adjusted adult cats.

- Young Adult – Young adults are aged between about 1 year and 6 years of age. Cats will still develop and change during this time but at a much slower rate than when they were kittens. If your cat wasn’t spayed or neutered as a kitten, you should ensure it is done now. This is the life stage where cats can become aggressive with one another, so watch for signs of behavioral issues if you have multiple cats in your home. Early socialization, training, and bonding efforts will determine how sociable and friendly your young adult cat is, and from the age of around 12 months, most cats transition to adult food, which is more of a maintenance diet than a developmental one.

- Mature Adult – From the age of 6 up to the age of about 10 years old, cats are considered mature adults. Your cat may remain playful and active, but many become more sedentary around this time and can be more prone to weight gain and obesity, so it’s important to watch their diet and weight.

- Senior – Senior cats are those aged 10 or above, but it really does depend on the individual cat. Some may start to slow and age when they are as young as 7 or 8, but some will keep charging around like young kittens until they are 12 years old or more. Senior cats are more prone to health problems, so you should take them to the vet more often to ensure optimal condition and seek advice from a vet about the most appropriate diet for them.

The 12 Tips To Improve Cat Wellbeing

1. Get Them Spayed or Neutered

Spaying and neutering help prevent unwanted pregnancies, which is especially important in cats because females can have their first heat at the age of around 5 months. Kittens can have kittens, and this can cause considerable risks for both the mother and the young.

But spaying and neutering aren’t just beneficial because they prevent litters of kittens, they also reduce the risks of some serious health problems including womb infections and mammary cancer. Spaying and neutering also reduce the occurrence of some behavioral issues such as unwanted spraying, particularly from male cats.

You should try to ensure that your kitten is spayed or neutered by the time they reach 5 or 6 months of age, unless your vet recommends otherwise.

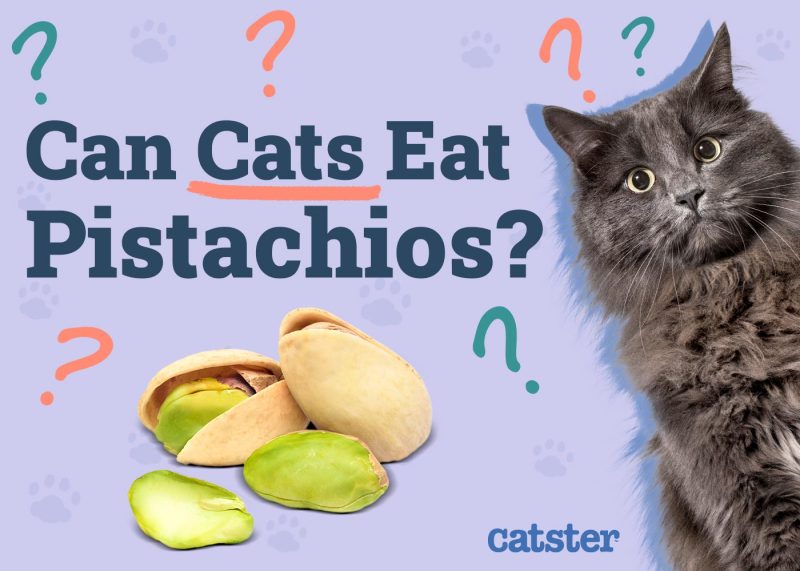

2. Feed a Good Diet

Once a kitten has been weaned off its mother, it should be given an appropriate kitten food formulated for their growth and development. Kitten food is higher in protein, and some other essential nutrients including fat and calcium. It also comes in smaller, bite-size pieces.

Depending on the breed and individual attributes of a cat, they will generally reach their full adult size between 6 months and 12 months, although some breeds like Maine Coons can take longer. When your cat reaches their full adult size and has effectively stopped growing, they can move to adult food. Senior diets are also available and there are various formulations with some designed to help other aspects of your cat’s health. Once your cat becomes senior (usually over the age of 10), it is a good idea to discuss with a veterinarian which diet would offer the best nutrition for your individual cat.

Need veterinary advice but can't get to the clinic? Catster recommends PangoVet, our online veterinary service. Talk to a vet online and get the answers and advice you need for your cat without having to leave your living room — all at an affordable price!

At all life stages you should offer a high quality, complete diet that has the AAFCO (Association of American Feed Control Officials) approval on the label. Cats are obligate carnivores and require specific nutrients found in meat, such as taurine, in their diet. It is also important to feed the right amount of food to avoid obesity related issues such as osteoarthritis and diabetes.

3. Set Routines

Most cats are creatures of habit, and you will also benefit from setting routines early in your cat’s development.

Your daily routine can involve feeding time, as well as the times your kitty will be allowed out and encouraged back in again. You can also include regular grooming and play sessions in these routines. Doing so not only provides your cat with structure and can reduce stress, but it makes it more likely that you will remember to meet your cat’s maintenance care needs.

4. Implement Good General Grooming

Cats are generally very clean creatures. They spend a lot of time grooming themselves, and keeping themselves as clean as possible. But they can’t do everything themselves. As their owner, it is your job to help them with what they can’t do.

Depending on the length and condition of your cat’s coat, it might need brushing daily or weekly. You will also need to monitor claw length and trim them if necessary. Brush teeth three times a week, at least, or daily, ideally. Check inside your cat’s ears and give them a gentle once over, checking for injuries or signs of fleas and ticks, regularly.

5. Get Them Vaccinated

Vaccinations help protect cats against certain illnesses and conditions, some of which can prove fatal if contracted. Core vaccinations are those that are considered essential, and you might even find that some insurance companies will refuse to pay out if your cat has not been properly vaccinated. Core vaccinations include feline calicivirus (FCV), feline herpesvirus (FHV-1), feline panleukopenia (FPV), and for cats under a year of age feline leukemia (FeLV). Rabies vaccination is also a core vaccination and a legal requirement in some areas.

Non-core vaccinations are additional vaccinations that can be used to protect against other conditions. Your vet will recommend if your cat is considered high risk for these conditions.

After the initial vaccination course, it is necessary to keep up with regular boosters, typically administered every year. If you fail to meet these annual requirements, your cat’s protection will wane, and they run the risk of getting ill.

6. Use Flea, Tick and Worm Preventatives

Appropriate parasite control is also very important. Kittens often get infected by internal parasites (e.g. roundworms) when they are nursing from their mother, and they can also be infected through their local environment.

External parasites such as fleas also need to be prevented. Your vet will recommend appropriate treatments for your cat and tell you how often they should be repeated to offer adequate ongoing protection.

7. Ensure Good Socialization

Cats need socializing when they are young to ensure they won’t be too afraid of people or anxious in new situations. Socialization means introducing your kittens to new people, friendly animals, and even new surroundings and situations in a gradual, positive way.

Start out slowly, to avoid overwhelming a young kitten, but don’t give up after a few meetings with friends and family. You should continue positive social interactions throughout your cat’s life.

8. Offer Regular Exercise

While you don’t necessarily have to walk a cat, like you would a pet dog, you do still need to make sure that your kitty gets adequate exercise. Outdoor cats can get a lot of exercise independently, but those who are kept indoors and not able to roam freely will need to get their exercise in different ways.

Use wand toys and other active toys to encourage your cat to chase and burn off energy. You can get cat exercise wheels, although not all cats take to using these, and you can even use cat leashes and harnesses so you can walk your cat outdoors, which is not only great as a means of exercise but also offers socialization and enrichment.

9. Provide Stimulation Through Toys

As well as toys that require your involvement, you will need to provide safe toys that your cat can use for independent play. Playtime is not only fun for your cat, but it enables them to exercise their natural instincts, therefore providing mental stimulation. When your cat is chasing a ball or throwing a soft mouse toy around, it is mimicking the chase involved in wild hunting.

You can also get interactive toys, which dispense treats when your cat completes a challenge. These are especially good for intelligent cats who need an outlet for their mental intelligence. Interactive toys can keep your cat busy while you’re out, which can reduce boredom and anxiety from being left alone.

10. Offer Scratching Opportunities

Another activity that naturally mimics cats’ wild instincts is scratching. Scratching helps maintain claw and physical health. It is also an effective means of marking or claiming territory, and some cats use scratching as a method of reducing anxiety and stress. They can also help prevent your cat from scratching and ruining furniture, floors, and even your legs. Cats also enjoy the vertical space that cat trees provide.

Buy good scratch posts, scratch mats, or other scratching products. Put them in your cat’s favorite rooms or, if you’re looking to correct inappropriate scratching, next to the item that you want to protect. It might take your cat some time to warm to the idea of a scratching post, but most kitties get the hang of it. You can always try sprinkling some catnip on the scratcher.

11. Bond Through Playtime

Playtime isn’t just a great way to burn off energy or stimulate your cat’s intelligent little brain. It also represents a great way for you and your feline friend to connect and bond with one another. Choose toys like wand toys, or even consider training your cat to play fetch.

Fetch might be most often associated with dogs, but a lot of owners have successfully taught their cats to play the simple game, and the training technique is similar. Working together to learn a new task is a great way to form a lasting bond between you and your cat.

12. Have Regular Checkups at the Vet

You will need to take your cat to the vet for its vaccinations and when ill or injured, but you should also take them for regular checkups. Kittens and senior cats should have more frequent checkups because these can identify small issues before they become major problems. Adult cats benefit from annual checkups, while young and old cats can go twice a year, as well as when required.

Conclusion

Cats make great companions. They are more independent than dogs but offer greater interaction than a lot of small animals. They also have a good lifespan and can live up to 20 years or more, as long as they are cared for and enjoy appropriate stimulation, enrichment, routine healthcare and veterinary treatment when required. Above are 12 steps and tips to help improve every life stage of your cat so that you can enjoy a long fulfilling life together.

Featured Image Credit: evrymmnt, Shutterstock