Click to Skip Ahead

Vaccines are designed to protect against a variety of feline diseases, including rabies virus, feline leukemia virus, feline distemper (also called parvovirus), feline calicivirus, and feline herpes virus.

One of the best ways to keep a cat healthy is to ensure that they get the specific vaccines they need, which should be discussed on an annual basis with their vet. Vaccines can consist of core and non-core vaccines, depending on a cat’s lifestyle (i.e., indoor vs outdoor, how often they might board in a cattery, etc.), age, and other risk factors. Core vaccines are designed to protect against infectious diseases that are either life-threatening or commonly encountered by the majority of cats. Non-core vaccines are those which may not be needed, depending on a particular cat’s risk factors.

To find out which vaccines an indoor cat generally needs and the timing of these vaccines, read on!

How Do Vaccines Work?

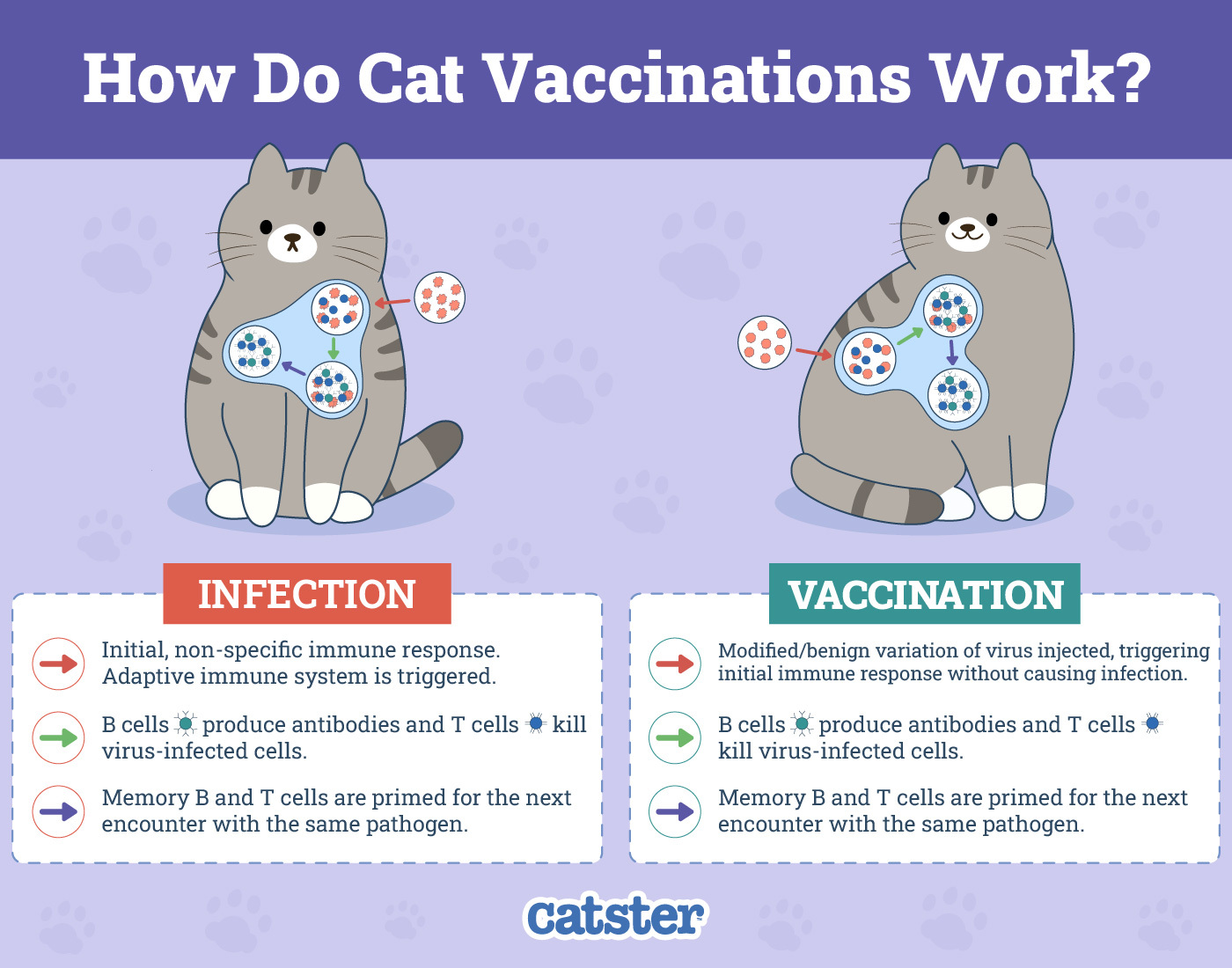

Some vaccines, called “killed” vaccines, contain inactive DNA or RNA from a pathogen, such as a virus or bacteria. Some vaccines, called “modified live” vaccines, contain less pathogenic forms of the normal virus or bacteria. Other vaccines, called “vectored” or “recombinant” vaccines, contain only a small part of a virus or bacteria inserted into an organism, called a plasmid, that acts to amplify this portion of the virus or bacteria once an animal is vaccinated.

Modified live and killed vaccines are some of the original, more traditional vaccines. Vectored vaccines are a more recent scientific development. Each type of vaccine has possible pros and cons.

After receiving a vaccine, the body recognizes the foreign material contained in the vaccine and produces an immune response. This response takes about 7–14 days to reach a peak response. This has to do with why vaccines are timed 3–4 weeks apart—to allow for this response and then a settling of the immune system before challenging it again with another vaccine.

Some vaccines made to combat infectious diseases that cats don’t routinely encounter, such as rabies, are considered effective after a single dose. Conversely, vaccines made to fight viruses that cats do commonly encounter or that may have antibodies received from their mom generally require a minimum of two doses, sometimes more, depending on the cat’s age.

What Vaccines Does an Indoor-Only Cat Need?

To determine what vaccines an indoor cat requires, they first need to be separated into kittens and adults.

Kittens receive their first vaccines in what is called a “primary vaccine course”. This involves vaccines that generally start around 8 weeks of age and continue every 3–4 weeks until they are 16 weeks of age or older. After 16 weeks of age, most kittens then need their next vaccine one year later.

- 8 weeks

- 12 weeks

- 16 weeks

Primary vaccines in kittens include their core vaccines (e.g., parvovirus, herpesvirus, and calicivirus), and potentially feline leukemia and rabies—depending on where they live, and their lifestyle risk factors. Rabies vaccines cannot be given to kittens until they are at least 12 weeks old.

Adult indoor cats fall into two categories for which vaccines they might need. Adult cats that have never been vaccinated generally get primary vaccines (just as a kitten would), along with a single booster 3–4 weeks later. The reason for this booster is that a single vaccine for herpes, calicivirus, and panleukopenia may not be fully effective—therefore, a second vaccine provides a bit more protection. Rabies, on the other hand, produces good results after a single vaccine, making a single vaccine sufficient.

Adult cats that received their primary course as kittens generally receive boosters either annually or triennially, depending on the vaccine, how much time they spend outside or boarding with other cats, as well as their age.

What Are the Minimum Vaccines My Indoor Cat Needs?

Once they are an adult, an indoor-only cat that lives in an area without rabies may only need the following vaccines:

- Feline parvovirus

- Calicivirus

- Feline herpesvirus

The above may be given every three years for some low-risk cats. However, it is always a discussion to have with your veterinarian to determine what vaccines and what vaccine schedule your cat needs.

Are There Instances Where a Cat Vaccine Schedule Might Change?

There are certain instances in which a cat may be deemed not healthy enough to receive a vaccine. Alternatively, it might be too early for them to receive a vaccine. A veterinarian may choose to delay vaccination of a cat for the following reasons:

- Weight loss

- Not eating

- Urinary tract infection

- Upper respiratory infection

- Vomiting

- Diarrhea

- Too soon from the last vaccine

If you are concerned or have questions about your cat’s health, you can also speak to a vet from the comfort of your own home to help make a plan. They can determine when an in-clinic vet visit should be made.

If you need to speak with a vet but can't get to one, head over to PangoVet. It's an online service where you can talk to a vet online and get the advice you need for your pet — all at an affordable price!

Frequently Asked Questions

What are possible vaccine side effects?

Vaccines, as with any medication, can have potential side effects. One of the more well-known side effects, particularly in cats, is called vaccine-associated fibrosarcoma. Fibrosarcoma is a cancer that forms from the cells forming the connective tissue layer under the skin. There is strong evidence to suggest that a combination of genetics, certain vaccines, and vaccine adjuvants can lead to the formation of these cancers in cats.

Many of these vaccines are now made in a different manner, to not contain adjuvants, and most vaccines in cats are also now given in specific locations of the body—so that if one of these cancers occurs, the vaccine that may have played a role can be identified.

Some common side effects of vaccines in cats include lethargy, vomiting, and diarrhea. Cats rarely develop anaphylaxis, or life-threatening allergic reactions to vaccines, facial swelling, and hives, the same way many other species are prone to developing. If your cat does experience any reactions to a vaccine, report it to your vet, as the way your cat is vaccinated may need to be adjusted moving forward.

How are vaccines given?

Most vaccines for cats are injections given under the skin and are generally about 1 ml in volume. Other forms of vaccines include nasal drops and transdermal vaccines, but these are uncommonly encountered.

My cat is late for their vaccine. Does that change the schedule?

It depends. If your cat’s a day or two late, or even a week late, for their annual booster, it is generally not a problem. If your cat’s more than a week or two late for their primary course booster, they may need an additional booster vaccine.

Is my cat too old for vaccines?

Generally, veterinarians no longer consider cats “too old” for most things. Sometimes, senior cats need the immunity provided by vaccines far more than adult cats. Discuss what risk factors exist for your senior cat—such as time spent outside, boarding around other cats and dogs, and any medical conditions—with your veterinarian to determine which vaccines they recommend and how often.

Conclusion

Vaccination in indoor cats is important in preventing serious illness and keeping our furry friends healthy. Vaccines are not just something done once when they are kittens; they are part of a lifelong health plan for your cat.

Featured Image Credit: Africa Studio, Shutterstock

My cat is five years old and received her shots about three years ago before I got her.. The vet keeps texting me to get her in for more shots. She is an indoor cat and has no other animals living with her. She is fed a steady diet of Royal Cabin D food plus a treat of Churu.

I am 90 years old, live alone and am disabled. I have no one who can help get her in to the vet.

How much risk to her health if she doesn't get more shots? J

Hi John Benzon, beyond protecting your cat’s health, some of our pets shots, for example rabies, are required by law. You would need to find out what vaccines your vet is recommending to understand their urgency and importance as well as the potential risks for your cat. If you need guidance from a vet from your home, you can try contacting www.pangovet.com. They can help you through the next steps. But chances are you will need to either get someone to take you cat to the clinic or find a vet that offers house calls.