In this article

View 2 More +Every living being poops, including cats, so pooping should not be a taboo subject. Owners need to know how often their cats should poop to understand what is healthy and unhealthy. This way, cat owners can ensure optimal health and longevity for their cats in the long run. So, how often should a cat poop? As a general overview, cats should defecate at least one time a day, but it all depends on your furry friend’s age. If you would like to know more details and facts, read on!

Healthy Poop Schedules for Cats

The truth is that there is no one set of rules that cats must follow to stay healthy when it comes to their digestion. A general rule of thumb is that cats should defecate at least one time a day. Younger cats tend to go more often. But depending on several factors, cats may poop more often, but rarely less. What really matters is that your cat is pooping regularly. If their pooping habits change, there may be an underlying medical condition to blame, and a veterinarian should be consulted as soon as possible.

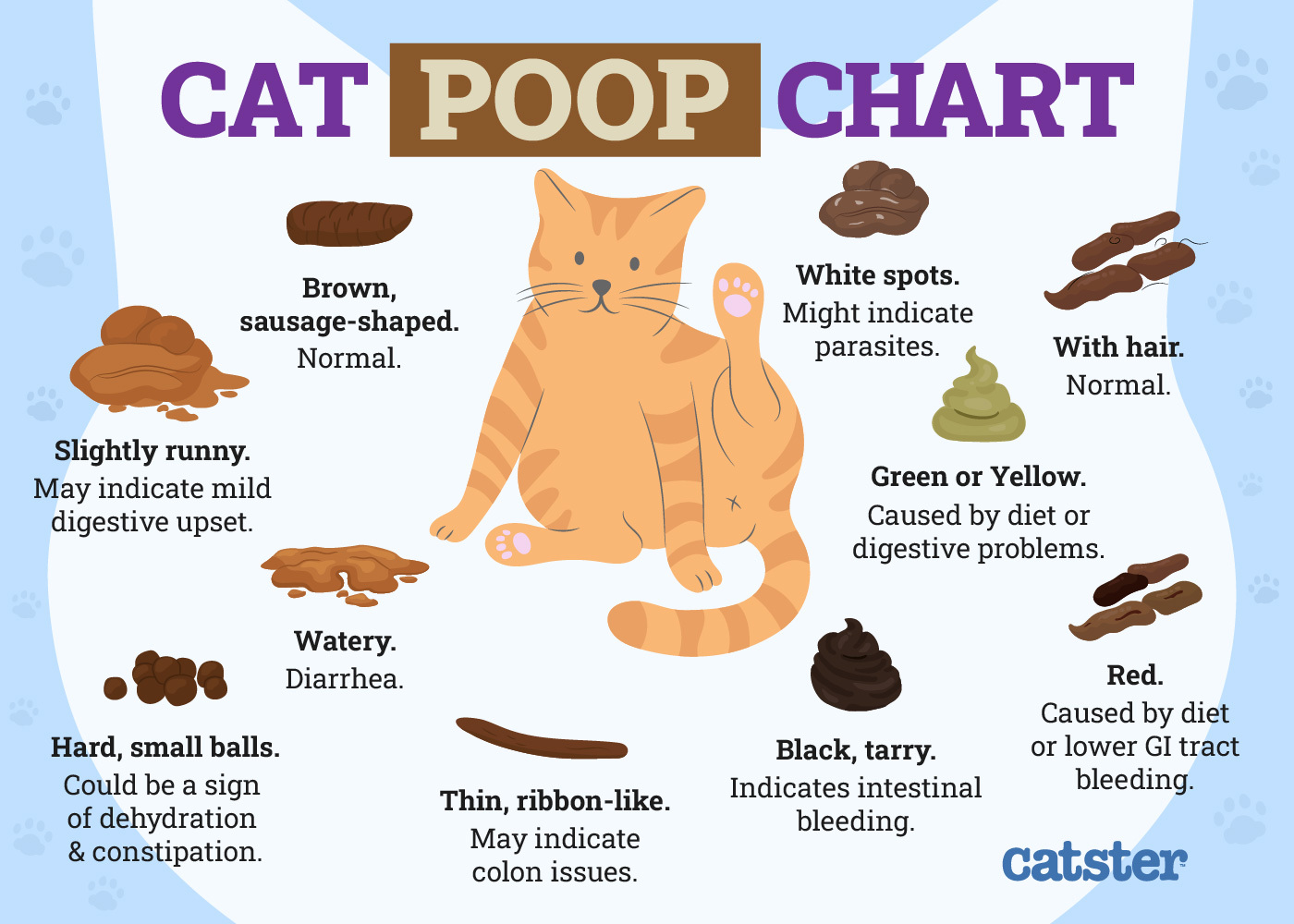

The quality of the poop is also something to pay attention to. If your cat is pooping regularly but the condition of their poop changes, there might be a problem. Irregularities and pooping conditions both need to be considered when determining whether your cat’s digestive system is working properly.

What Healthy Cat Poop Looks Like

Healthy cat poop is fairly solid but not too soft or hard. It should be malleable, like clay. The shape should be slightly S-shaped and medium brown. Any mushy or runny stool could mean that your cat is stressed, has a bacterial imbalance, has an infection, or, for another reason, is drinking too much water, which could lead to electrolyte imbalances. Food allergies, food sensitivities, a change in diet, colitis, and inflammatory bowel disease are all health conditions that could result in runny stool.

Hard stool is usually due to constipation and a lack of hydration. However, it could be a symptom of a more severe problem, such as a colon blockage or a metabolic condition. Black stool can mean that blood is present and internal bleeding is occurring. A stool that is too light in color could mean a problem with the pancreas or gallbladder. It may also mean that food is not being properly digested in the gut.

If you notice any irregular coloring or consistency for more than a day, it is a good idea to schedule a checkup with your veterinarian to figure out why your cat’s poop has changed. Your vet should be able to identify the underlying cause of your cat’s pooping irregularities and help you make the necessary and proper corrections.

If you need to speak with a vet but can't get to one, head over to PangoVet. It's an online service where you can talk to a vet online and get the advice you need for your pet — all at an affordable price!

The 4 Things That Can Affect Cat Pooping

There are a variety of things that can affect your cat’s poop quality, from health problems to changes in diet. You can figure out the cause if you understand what could be to blame for your cat’s stool issues.

1. A Change in Diet

Suddenly changing your cat’s diet could cause your cat’s stool to change in consistency and timing, at least for a few days. A small amount of the new food should be mixed with the old food for a few days. Then the mixture should become half and half for a few days, and so on. Eventually, the old food is completely phased out, and the new food is completely phased in. If this does not happen, chances are that your cat will have poop problems for a few days. If, for reasons out of your control, you had to change your cat’s diet abruptly, give them a few days to adjust before assessing their stool. If a week passes and their stool does not go back to normal, it is time to consult a veterinarian.

2. Too Much or Too Little Water

If your cat is not getting enough water, their stools could not only be hard in consistency but also hard to pass. Your cat may poop less often, and they might show signs of straining while trying to defecate. If your cat has not pooped in 48 hours, this is considered a sign of constipation. To prevent this, your cat should be provided with a bowl of fresh drinking water at all times. Their water dish should be refreshed daily to ensure that your cat will drink it when they need to. Most cats will not drink water that they deem to be dirty.

Too much water can cause an entirely different reaction and could result in loose stool. Your cat could be getting too much water if they have an underlying health condition, such as diabetes or hyperadrenocorticism, that makes them drink more water from their water dish than should be necessary for their health. If your cat is drinking more water than you think, they should consider consulting your veterinarian. If they are not drinking enough water, try refreshing their water bowl more often and offering high-moisture cat food and moisture-rich treats throughout the day.

3. Anxiety or Stress

Cats with anxiety or stress may exhibit problems when it comes to pooping. Either of these mental conditions can contribute to constipation. If you move to a new house, a new baby or person joins your household, sleeping arrangements change, or new pets move in, chances are that your cat will get stressed out and anxious for some time. If this is the case, your cat might not poop normally for a few days. But improvements should be seen within about a week.

4. Health Problems

Your cat may also experience problems pooping properly if they are experiencing health problems. Organ disease, diabetes, cancer, and even neurological issues can inhibit the health of your cat’s digestive system and pooping regularity. If you cannot find a logical reason for your cat’s poop problems, there is a chance that the problems are due to an underlying health problem. Your veterinarian can confirm or eliminate any health problems that are suspected.

Our Final Thoughts

Now that you know what is and is not normal when it comes to cat poop, you can better gauge the health of your cat as they age. If you are ever in doubt, reach out to your veterinarian for expert advice and guidance. What do you think about how defecation and health intertwine when it comes to your cat’s health? Enlighten us with your thoughts in our comments section!

Featured Image Credit: Axel Bueckert, Shutterstock