The genetics of feline coat colors and patterns are extremely complex, and also include one of the most unique features in the animal kingdom, whereby the genes for the colors black and orange are located on the X chromosome, quite separate from the rest of the code for coat variations, which are all located on one region known as the KIT-gene. These complicated interactions provide endless possibilities when it comes to the feline appearance, but a recent discovery has revealed that there are still more combinations and colors to be explored, and soon “salty liquorice” will be known as more than just a sweet and salty snack.

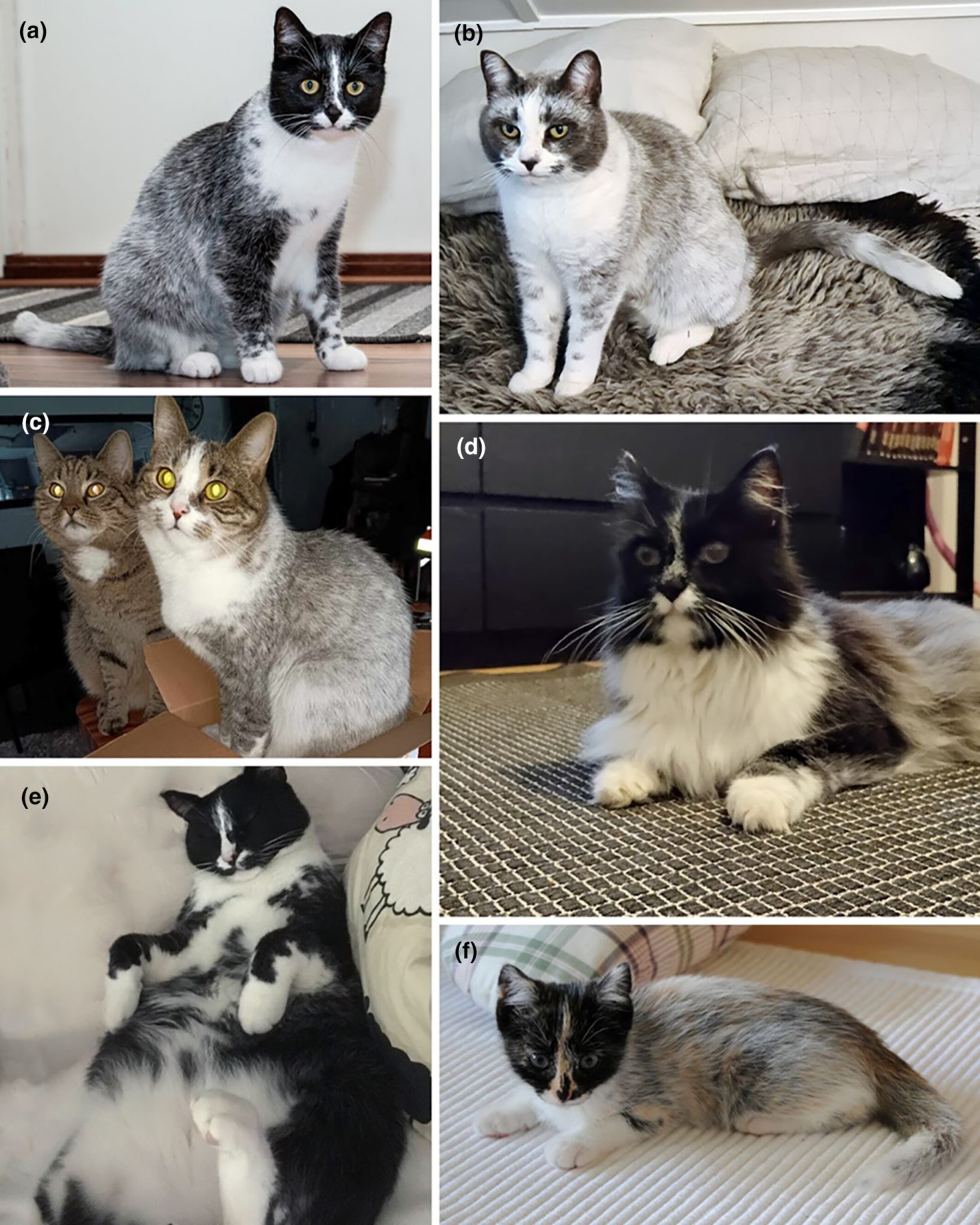

Over the past two decades, an unusual variant of the black and white coat color has been emerging within a population of cats found in central Finland. Similar in appearance to a classic tuxedo coat pattern, this new variant had irregularities in the pigment distribution, creating a finely mottled appearance of the fur that would ordinarily be solid black. This unusual pigmentation has also been seen overlying other patterns, including tabby, tortoiseshell, or diluted (blue) coats. As more cats started to appear, a team of researchers in Helsinki decided to take a closer look at these fancy felines, and by close, we mean at the molecular level.

(b) salmiak solid blue cat (diluted black, aa/dd/wsalwsal)

(c) salmiak brown mackerel tabby (wsalwsal) (right) and his normal-colored brother heterozygous for salmiak (wsalw)

(d) salmiak phenotype on a long-haired solid black cat (not genotyped)

(e) salmiak solid black cat (aa/wsalwsal)

(f) salmiak phenotype on a tortoiseshell cat (not genotyped)

Photo credits: (a) Ari Kankainen and (b–e) courtesy of the cat owners

What researchers found when examining the KIT-gene of these mottled cats, affectionately labelled “Salmiak” after the popular salty liquorice Nordic snack, was that they possessed a completely new variant of the white (W) code. Having identified the salmiak variant (Wsal), they were then able to locate the same genotype in non-salmiak cats, confirming that the salty liquorice trait is the result of a recessive gene, requiring two copies – one from each parent – to appear.

Despite the seemingly endless variations of feline coat appearance (phenotypes), there are actually only three core colors at a genetic level – black, orange, and white, with the latter more accurately classified as the ‘absence of color’. The way in which the ‘white’ gene is expressed (genotype) dictates how and where pigment will or will not appear. Different shades of colors are created through the presence of a ‘dilution’ gene, while other gene variations will determine how the pigment is expressed along each hair shaft. The genetics of feline coat colors is not easily condensed into anything shorter than a textbook, but we have included a very brief summary of some key points at the end of the article, should you wish to know a little more.

All cats displaying the salmiak markings have either yellow or green eyes, the most common eye colors in cats. Initially, it was theorized that the double Wsal genotype was linked to sterility; however, the birth of a litter of kittens to a salmiak-coated cat disproved this hypothesis!

It is likely that as word spreads about these beautiful felines that their popularity will increase. However, we would recommend caution before ordering yourself a sweet & salty cat, as there is always an increased risk of heritable disease when selectively breeding individuals with recessive genes. At this stage, no specific health conditions have been linked to the salmiak appearance; however, the population is too small to draw any meaningful conclusions regarding possible associated mutations.

The Genetics of Cat Colors

Cats have two primary pigments: eumelanin (responsible for black or brown colors), and pheomelanin (which produces red and yellow hues). When we look at the genetics behind coat color variations, each gene is defined by two letters that represent the form of the gene (alleles) from each parent. These determine what pattern and pigment their offspring will be. The dominant allele has a capital letter, while the recessive allele is shown in lowercase.

Brown (B/b/b’)

Determines eumelanin production. Cats with the dominant B allele will have black fur, while cats that inherit a double copy of the recessive b or b’ alleles will usually have chocolate (b/b or b/b’) or cinnamon (b’/b’) fur.

Orange (O)

Located on the X (female) chromosome, which means that male (XY) cats can either be orange or not, while females (XX) can be orange, non-orange, or a mix (tortoiseshell). This is a trait unique to cats and means that, with the exception of rare chromosomal abnormalities, all tortoiseshell cats are inherently female.

Dilution (D)

This affects the intensity or shade of a color. Cats with the D (dominant) allele have the protein melanophilin, which is what deposits pigment into the fur, resulting in full-intensity color. The recessive allele (d) of melanophilin’s presence results in the lightening of the color, turning black into gray (aka blue), chocolate into lilac, cinnamon into fawn, and orange into cream.

White (WD) and White spotting (Ws)

White is not actually a color, but the lack of color, and WD will mask all other colors, resulting in a completely white cat, but it is different from albinism. The WD gene can also be linked to deafness. Cats with the Ws gene can range from almost completely white to having just a few white spots.

- The genotype is the letter representation of the trait – e.g., B/b

- The phenotype is the outward appearance of that trait – e.g., black

Feature Image Credit: Ari Kankainen

Did You Know?

- Our breaking news articles are featured in our weekly emails. Don’t miss out on the latest and sign up for our newsletter below!