Are you crazy about cats? If so, there are tons of cat-themed purses you may want to try out. Surprisingly, cat-themed purses are pretty common, so you should have no problem finding something that you like.

We’ll list our favorite cat-themed purses below so that you can find the one you like the best.

Top 10 Cat-Themed Purses

1. Afkomst Small Crossbody Purse

This little pink purse is very classy while also being obviously cat-themed. It features a cat nose and whiskers and a light pink background. It goes with a lot of outfits and doesn’t necessarily scream “crazy cat lady.”

This bag isn’t terribly expensive, either. It’s about what you’d expect from a purse of this size. It’s a rather small bag designed primarily for carrying smaller items, such as just a wallet and your phone.

We liked that the strap is very adjustable, allowing it to fit just about everyone. Of course, we still recommend having a look at the dimensions, just in case.

2. Gadmexily Black Cat Crossbody Purse

This sleek purse is a great option for someone who wants something particularly “catty.” It’s fuzzy with two very obvious cat eyes and ears. There are even some whiskers added. Like many bags on this list, it is made to be worn across your body.

The size is a bit bigger than other purses, allowing you to carry more things. However, the shape is a bit more awkward than other purses. It is extremely round, so it isn’t very efficient with its space.

The strap is pretty adjustable, so it will fit most people.

3. Gladdon Crossbody Cat Bag

This cat-themed purse is very simple. It’s just a black bag with a simplistic cat face on it—ears, nose, and whiskers. It’s not fuzzy like some other cat bags. Instead, it’s made with a soft synthetic fabric that holds up decently well. It isn’t the best quality, though, so it likely won’t last as long as many of the other purses out there.

This bag is also small, like many of the purses on this list. It is big enough to hold some very small items, though, such as a phone and wallet.

4. Mibasies Kid Cat Purse

This colorful purse is designed for children, as you might guess from the title. It’s the color of a pastel rainbow, which smaller children are sure to like. It is available in several different colors, but they are all rainbow. The shades and tones just differ.

That said, this bag is very small. It’s made for children, so that isn’t very surprising.

5. Valentoria Mini Faux Leather Cat Purse

Unlike other purses on our list, this one doesn’t have a strap. Instead, it’s a simple clutch wallet that’s made to carry your money, keys, credit cards, and other items. It features three eccentric cats on the front, making it a great option for anyone who is cat-obsessed. It’s a bit smaller than other purses on this list, but it isn’t made to hold that much stuff.

The inside is full of pockets and places to put your cards. It’s easily one of the more organized options on this list. If you want a clutch wallet instead of a full purse, we recommend it.

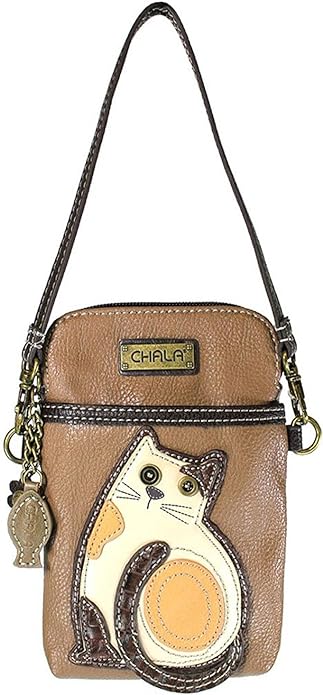

6. Chala Crossbody Cell Phone Purse

This very eccentric purse is great for someone who is looking for something a bit different. It features a gray cat with a small fish. The cat has buttons for eyes, and the whole thing has a very antique feel to it. If that’s the style you’re going for, this small purse may be a great option.

Of course, with that said, this bag is very small. It’s only made to carry a few items, like most purses on this list.

There are several versions of this bag, as well. Not all of them feature cats, but several of them do. All of them have the same antique, hippy vibe, but the designs and colors are different.

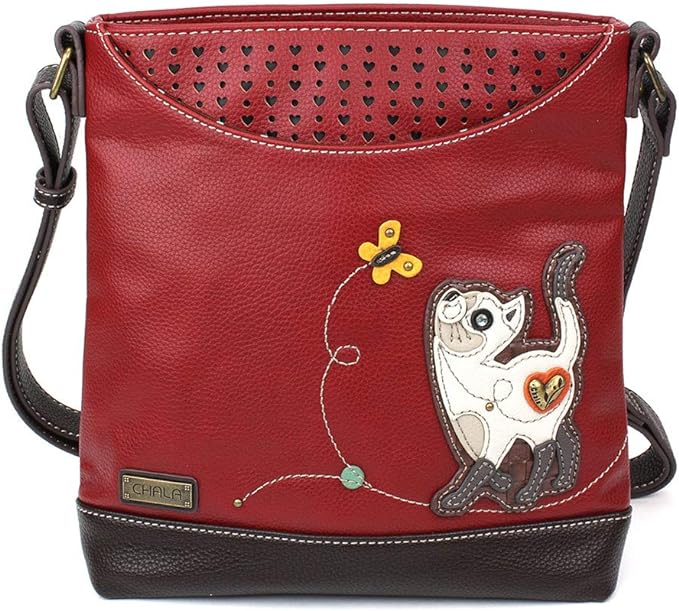

7. Chala Handbag Mid-Size

This bag is extremely similar to the previous one on this list. However, it’s larger, making it better for those who need to carry more stuff around. The company claims it is a “mid-size” bag, but it is a bit smaller than what we’d consider “mid-sized.” Yes, you can fit quite a bit in it, but there are tons of larger bags out there.

There are several colors available. Only one has a cat on it, though. This particular bag is red and features a small yellow butterfly on it, as well.

It’s made for you to wear cross-bodied, and it’s made from faux leather. It’s a pretty durable bag, but it is also cheaper than most options out there.

8. Laurel Burch Crossbody Tote

If you want an artful option, this tote is a solid choice. It’s larger than most, though it doesn’t include made inner pockets. It’s mostly just one big bag, though that isn’t necessarily a bad thing. It has two cats on the outside in a very artful pattern, as well as a tribal pattern across the rest of the bag.

This bag is much cheaper than other options despite being larger. It isn’t made as well as other bags and isn’t faux leather, which is likely why it is cheaper. However, it is a great budget option for those who want a more interesting bag.

9. Chala Brown Cat Bag

This Chala bag is another popular option from the company mentioned above. It’s a rather simple brown bag with a huge cat on the front. If you want something that has an obvious cat on it but isn’t as complex as some of the other bags, this purse is a great option.

There are some other color options, but only one has a cat on it. There is one with a pawprint, though, which may be vaguely considered to be a cat. Most other bags are dog-themed or include more neutral decorations like flowers.

This design is very unique and likely to stand out. Plus, it features some nice organization pockets on the inside, making it very practical, too.

10. Valentoria Canvas Handbag

This bag is fairly simple and inexpensive. It features two cute cats embroidered on the front. It’s also very practical, with plenty of internal pockets for you to hold your phone, purse, and other items. It’s much larger than most bags on this list, but it’s very reasonably priced. It’s easily one of the more practical bags on this list.

The company makes the bag in several colors, and all of them feature a cat on the front. You can get this bag in blue, brown, tan, red, or a range of other colors.

Conclusion

If you’re a cat lover, there are plenty of cat-themed purses for you to choose from. Whether you want something more eccentric or a simple design, there is someone out there making it. Our list above provides a huge range of options, and we hope you found something you love.

Featured Photo Credit: Andrejs Marcenko, Shutterstock

Contents

- Top 10 Cat-Themed Purses

- 1. Afkomst Small Crossbody Purse

- 2. Gadmexily Black Cat Crossbody Purse

- 3. Gladdon Crossbody Cat Bag

- 4. Mibasies Kid Cat Purse

- 5. Valentoria Mini Faux Leather Cat Purse

- 6. Chala Crossbody Cell Phone Purse

- 7. Chala Handbag Mid-Size

- 8. Laurel Burch Crossbody Tote

- 9. Chala Brown Cat Bag

- 10. Valentoria Canvas Handbag

- Conclusion